This post contains affiliate links, meaning if you click through and make a purchase, I may earn a commission at no additional cost to you.

The Basque language, Euskara, is an endlessly fascinating subject.

Just as I’ve been obsessed with my Basque heritage since childhood, so have I been strangely obsessed with Napoleon Bonaparte.

So when these two interests of mine slightly overlap, I’m all over it.

But if you’re not a big fan of Napoleon, fair enough. He was kind of awful.

This story is really about his nephew anyway.

Louis-Lucien Bonaparte

Prince Louis-Lucien Bonaparte, son of Napoleon’s brother Lucien, spent much of his life studying and documenting the dialects of the Basque language in the 19th century.

Born in exile in England in 1813, Bonaparte was a philologist who studied many of the languages of Europe but with a particular focus on the Basque language. He studied Basque more in-depth than any other language he researched.

Bonaparte established the first extensive studies of the Basque language and laid the foundation for Basque linguistics.

During the French Second Empire, when his cousin Napoleon III was elected the first President of France, Bonaparte received the title of Prince. With this honor came an annual allowance.

Because of this stipend, in combination with some prizes he received for his work and a family inheritance later in life, Bonaparte was able to dedicate his work to his passion of studying different languages and dialects.

Despite having a degree in chemistry, Bonaparte’s involvement in politics introduced him to a love of languages that would make an indelible mark on his career and legacy.

While married to his first wife for over 60 years, Bonaparte spent much of his life living with his mistress, Clémence Richard, who helped him greatly in his research.

She had many connections to families in the Basque Country, had a good mastery of the Basque language, and introduced him to many of his assistants and research collaborators.

Research in the Basque Country

Bonaparte visited the Basque Country five times between 1856 and 1869, spending a total of nine months in the region.

During his first visit alone, he met and gathered a group of Basque collaborators who would assist him in his research for the rest of his life. And from this trip he was able to publish two books and prepare two additional manuscripts of his findings.

It’s unclear how well Bonaparte spoke Basque himself and was able to debate the nuances of Basque dialects. But he was prolific in gathering information about Basque dialects, working on translations, and publishing his findings.

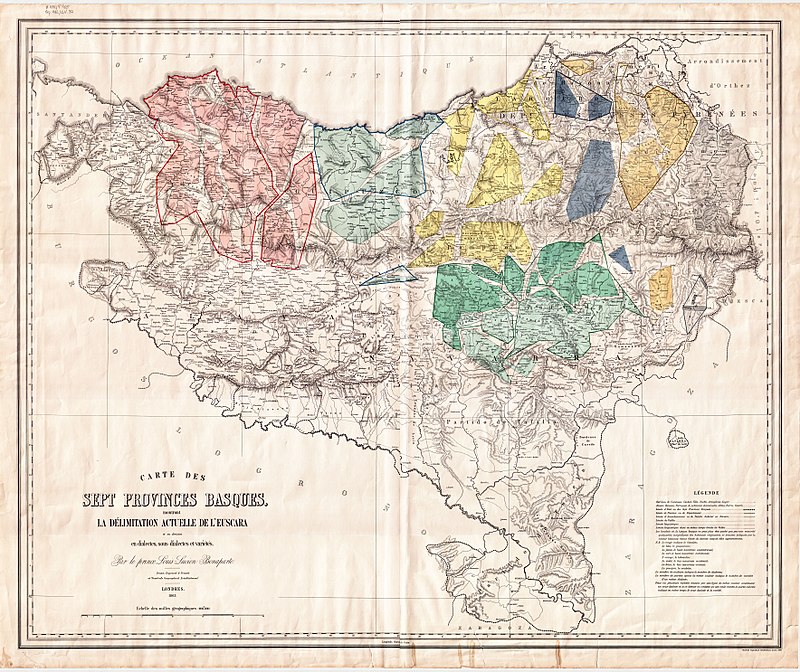

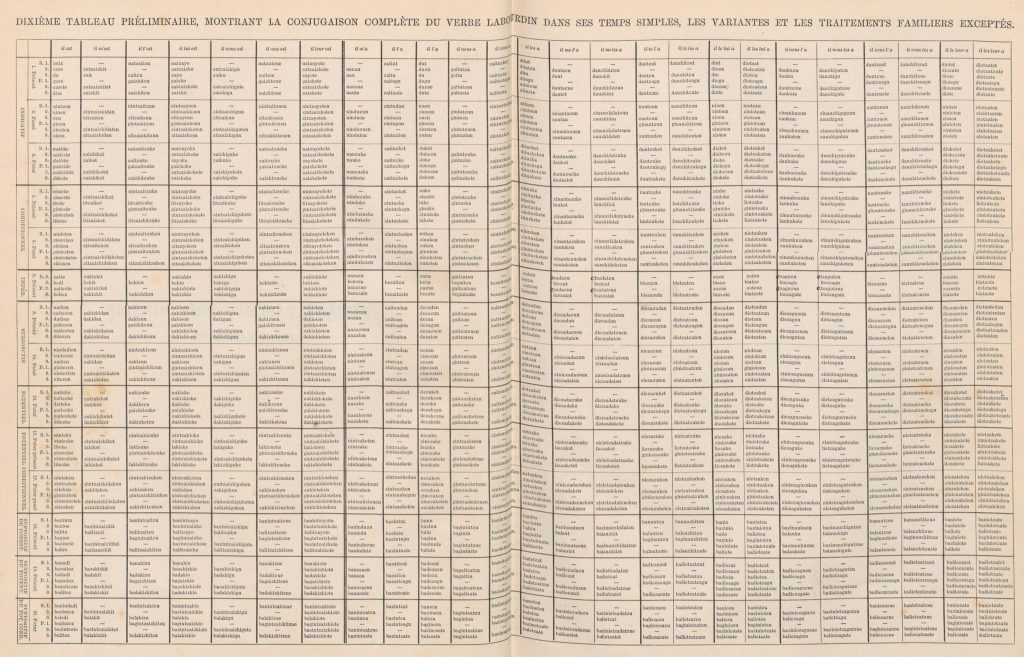

In classifying the Basque language, Bonaparte found there to be eight Basque dialects in his 1869 Le verbe basque en tableaux. He also published this finding along with a map of the Basque Country identifying these dialects.

Bonaparte based his research on the first Basque grammar by Manuel de Larramendi, El impossible vencido, published in 1729.

Using this as a reference in his work, he classified Euskara into the following dialects:

- Biscayan

- Gipuzkoan

- Northern Upper-Navarrese

- Southern Upper-Navarrese

- Western Lower-Navarrese

- Eastern Lower-Navarrese

- Souletin

- Labourdin

Within these dialects, he classified 25 sub-dialects and 50 variants.

If you’re struggling to grasp what a monumental task this was, take a look at one of the pages on verb conjugations in the Labourdin dialect.

Yikes!

You can actually flip through a manuscript of this massive text on Bilketa’s website if you’re curious.

In the 1998, linguist Koldo Zuazo provided the first major update to Bonaparte’s work by concluding Euskara actually has five dialects:

- Western

- Central

- Navarrese

- Navarrese-Labourdin

- Souletin

Among these, Zuazo also identified 11 sub-dialects and 24 variants.

An Extensive Body of Work

Along with the legacy of being the first to classify Basque dialects, Bonaparte also grew a large collection of books for his private library, which was estimated to be more than 25,000 volumes at his death.

The Newberry Library in Chicago bought much of the collection after his death for $21,000.

Bonaparte’s library contained many manuscripts he had written himself, 31% of which were devoted to the Basque language.

This included several translations of sections of the Bible, some written by Bonaparte but most commonly by the local experts he worked with, those native speakers of the dialects he studied.

In 1902 on a trip to London, the first president of Euskaltzaindia (the Academy of the Basque Language), R. M. de Azkue, found that these Basque manuscripts were still for sale.

With the support of the Spanish ambassador in London, Basque deputies and politicians, the manuscripts were bought for £350 and brought to the Basque Country in 1904.

So while Euskara is a mystery to many academics and laymen alike, we have Louis-Lucien Bonaparte’s work to thank for starting to uncover its layers.

While linguists and philologists have built on his work and the development of standardized Basque, Euskara Batua, has impacted the way Basque is spoken today, Bonaparte laid the groundwork for modern Basque linguistics.

Much of the information from this post was drawn from a 1991 speech by linguist Pello Salaburu. A big mil esker to Euskaltzaindia for providing it, and you can read the full lecture here.

CONTINUE READING:

- How Many People in the Basque Country Actually Speak Euskara?

- Euskara Thriving in the Basque Country with Euskaraldia

- How the Basques Defeated Europe’s Greatest Army and How History Erased Them

I found your internet site from Google as well as I

have to claim it was an excellent locate. Many thanks!

Hi Shad, so glad you found this site! Welcome! 😀