This post contains affiliate links, meaning, if you click through and make a purchase, I may earn a commission at no additional cost to you. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Today marks the anniversary of one of the Basque’s most successful military victories in history.

1,240 years ago today, on August 15, 778 AD, the Basques defeated Frankish king Charlemagne’s army at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass (Euskara: Orreaga).

Basque warriors ambushed Charlemagne’s rear guard as the Frankish army crossed the Pyrenees back into France, killing every last Frank. Some estimate the number of people killed in the rear guard to be around 2,000, with minimal casualties on the side of the Basques.

So how and why did this slaughter happen?

Sit back, relax, and let’s get into it.

Background

Why was Charlemagne such a big deal?

To understand what a massive deal this military victory was for the Basques, Charlemagne’s rule has to be be put into context.

To understand what a massive deal this military victory was for the Basques, Charlemagne’s rule has to be be put into context.

Charlemagne inherited the Frankish kingdom in 768 AD and set about expanding his land holdings. He was insanely successful at it.

So much so that his reign later inspired the likes of European megalomaniacs Napoleon Bonaparte and Adolf Hitler. (Creepy, right?)

Throughout his 46 year reign, the Charlemagne enjoyed unparalleled military victories, conquering most of western Europe. From the Atlantic coasts of France to the west, the northern half of Italy to the south, modern-day Austria and Germany to the east, and north all the way up to the North Sea, Charlemagne ruled it all.

RECOMMENDED READING Charlemagne: A Biography

One of Charlemagne’s main goals in expanding his kingdom, other than making himself super rich and powerful, was to spread Christianity. Which is just a nice way of saying forcing pagans to convert and killing those who refused.

Charlemagne was so good at expanding Christendom that the Pope at the time, Leo III, crowned Charlemagne Holy Roman Emperor on Christmas Day 800 AD. Thus, making Charlemagne the first emperor to rule western Europe since the fall of the Roman Empire in 476 AD.

What was Charlemagne doing on the Iberian Peninsula?

Charlemagne got word in 777 AD that several Muslim governors on the Iberian Peninsula were willing to submit to his rule in return for military aid against the emir of Cordoba, who ruled most of what we know as modern-day Spain.

While unhappy with the emir’s rule, the Muslim governors were also anticipating an invasion by the forces of the caliph in Baghdad. So they needed help fast.

Charlemagne agreed to send his army, ever looking for opportunities to expand his kingdom and win victories for Christianity.

He led his army into Spain across the Pyrenees through the Roncevaux Pass in the Basque Country (then known as Vasconia), while sending another section of his army through Catalonia to the east.

Charlemagne captured Pamplona and moved on to Zaragoza, where he was under the impression the governor there had pledged his allegiance to him. He was wrong, and the city remained closed to Charlemagne and the Frankish army.

Because of the less than warm welcome from the governor of Zaragoza, Charlemagne’s army laid siege to the city.

Photo: Roger Louis Martinez

One month later, the governor offered Charlemagne some hostages and an impressive amount of gold in exchange for the Franks leaving the city.

Around this same time, Charlemagne heard the Saxons he had just conquered, all the way on the other side of his empire, were in revolt.

Deciding Zaragoza wasn’t worth the effort when he had a kingdom in crisis to attend to, Charlemagne took the offer and marched his army back to the Pyrenees the way they had come.

Along the way back, Charlemagne had his army raze some Basque villages. Reaching Pamplona, he ordered the city walls to be destroyed because he suspected they could be used in the future for some local rebellion against his rule.

As Charlemagne and his army neared Roncevaux Pass, you can imagine the Basques in the region were a little more than pissed off.

RECOMMENDED READING Legends and Popular Tales of the Basque People

The Battle

On the night of August 15, 778, a large group of Basque guerilla warriors ambushed the Frankish rearguard.

Charlemagne and the rest of the army were further ahead across the mountains, but an estimated 2,000 people in the rearguard were outnumbered and overwhelmed by the Basque forces.

The rearguard held the Basques off enough to allow Charlemagne and the rest of the Frankish army to get across the mountains unharmed.

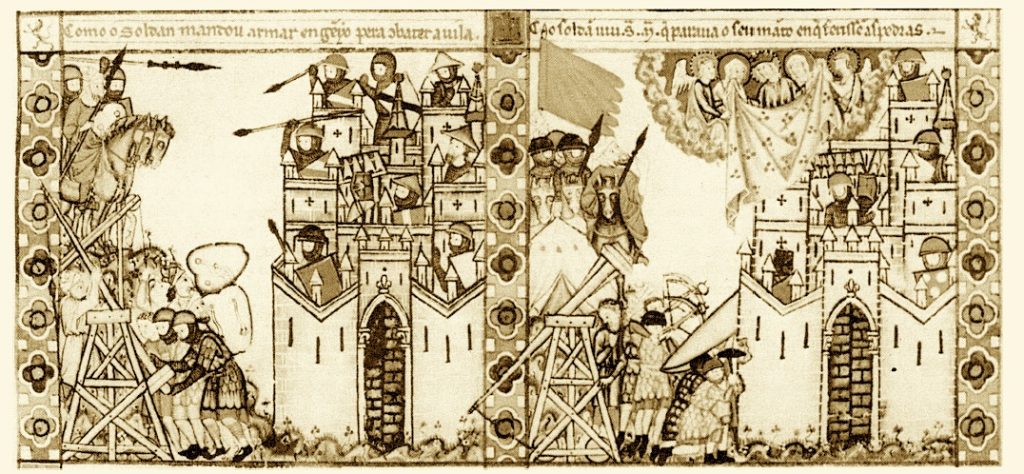

“The Battle of Roncevaux Pass, Sir Roland’s Death” from a 14th century illuminated manuscript at the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal

The Basque warriors were most likely ill-equipped and less skilled in battle compared to the professionally trained Frankish army, but they had the upper hand of knowing the terrain and using that to their advantage.

Roncevaux Pass is quite narrow, so Charlemagne’s army would have been spread out across several miles through the mountains.

Basque mountain warriors of the time typically armed themselves with two spears and a knife or short sword, with bows and javelins as missile weapons. The Frankish rear guard, on the other hand, would have been trained cavalry with chain mail and all.

Charlemagne’s rear guard included some Very Important Knights: Egginhard (Mayor of the Palace, i.e. a high-ranking government official), Anselmus (Palatine Count), and Roland (Governor of the Breton March).

Now, remember Roland’s name. He was kind of a big deal.

Ultimately, the Basques killed every last one of the Franks in the rearguard, looted their baggage, and set out with the gold from Zaragoza.

RECOMMENDED READING The Basque History of the World: The Story of a Nation

Significance

The Battle of Roncevaux Pass was arguably the only major defeat suffered by Charlemagne and his armies throughout his reign.

It was especially impressive, because “the Frankish army stands as one of the most dominant forces the world has ever seen” (History in an Hour).

After the embarrassing ambush, Charlemagne only sent generals to lead campaigns on the Iberian Peninsula for the rest of his reign, never returning to lead another army himself.

The Battle of Roncevaux Pass was immortalized in the French epic poem, La chanson de Roland (“The Song of Roland”).

(This is why you needed to remember Roland. Stay with me. We’re almost there.)

RECOMMENDED 9 Movies Filmed in the Basque Country

La chanson de Roland is the oldest surviving French text, written in the early 12th century. It recounts Charlemagne’s time on the Iberian Peninsula and culminates with the ambush of his rear guard and the dramatic death of his right-hand man, Roland.

La Mort de Roland by Jean Fouquet

Written centuries after the Battle of Roncevaux Pass took place, the epic Medieval poem greatly romanticizes the events that took place. The heroic and doomed figure of Roland became a model for all knights and chivalric duties during the Middle Ages.

The story was even told to the Norman army before the Battle of Hastings in 1066 to inspire the troops (spoiler alert: they won).

Despite its popularity and literary significance, La chanson de Roland presents an inaccurate portrayal of the Battle of Roncevaux Pass. In it, the Basque warriors are replaced by a force of 400,000 Saracens, Muslim people who inhabited the Iberian Peninsula at the time.

This edit was probably politically motivated because the Crusades were going on at the time. Muslims were seen as the enemies of Christendom, more so than the pagan Basques of the original Battle of Roncevaux Pass.

It is widely believed that Christian conversion of the Basques was fairly widespread by the 12th century, no longer making the Basques a pagan threat to Christianity.

European Travel Magazine says it best:

One can’t help but wonder if the Christian and feudal lords, that called for Crusades in that exact time in history used the poem to instigate hatred towards the treacherous Muslims and inspire young men to become brave knights.

Because if one knight [Roland] could hold off one-hundred-thousand-strong Muslim troops, slice off the hand of Muslim king and decapitate the king’s son, maybe another knight could do it too and become subject for yet another legend.

If you would like to read La chanson de Roland for yourself, you can find the English translation here and the French version here

.

Monuments of the Battle

The location of the Basque ambush on the Frankish army is much speculated. It is generally agreed the battle occurred above the town of Roncevaux/Roncesvalles/Orreaga itself, as that is the easiest and historically the most traditional route of crossing over the Pyrenees in the Basque Country.

There is a monument to Roland there, known locally as Ibañeta Pass.

Photo: Euskalduna

The town of Roncevaux/Orreaga itself also has a monument commemorating the battle, with a plaque in Latin, Spanish, and Euskara.

From what I can Google Translate, it appears the Latin inscription reads: “The Basques rose to the top of the highest mountain” (vascones in summi montis vertice surgentes). How poetic.

Photo: Cruccone

There are also a surprising number of monuments to Roland throughout Germany (which was once part of Charlemagne’s Holy Roman Empire).

From the 13th century onward, many towns in the Holy Roman Empire wanted greater autonomy from their noble rulers. Along the way, Roland became a symbol of this growing desire for independence, and statues of him cropped up in quite a few towns.

Most of the statues that remain today are from the 13th to 17th centuries, but there are some new ones too. Berlin has 6 Roland statues, and 4 of them are from the 20th century.

While Roland lived on in legend, the Basques were forgotten from the story. Historians aren’t even entirely sure of the names of the Basque warriors who led the ambush on the Frankish army, but Roland is remembered.

In literature, history books, songs, paintings, and statues.

The monument standing at Roncevaux Pass today is not one recounting a Basque military victory, but a memorial to Roland.

I think that speaks for itself.

Continue Reading:

- 9 Movies Filmed in the Basque Country

- The Ultimate List of Hollywood Movies Filmed in the Basque Country

- Paul Laxalt, Basque American Politician from Nevada, Dies at 96

Very well